by Sharna Goldseker, 21/64

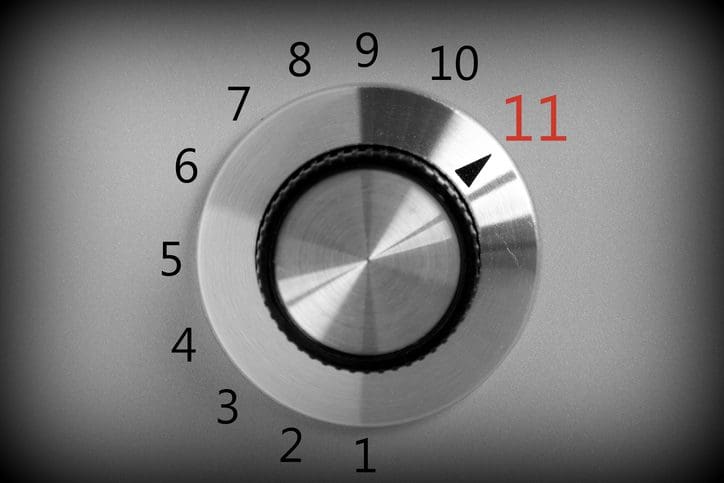

Whether you are new to philanthropy, or looking to engage your family, it’s valuable in the beginning to reflect on what you want to achieve with your philanthropy and invite family members into the discussion. The following 11 best practices in family philanthropy governance can guide you and serve as action steps when you are ready. For some, beginning this planning and talking with family members about it will feel easy to navigate. For others, working with your advisor might be useful at this juncture.

1. Clarify your Philanthropic Identity

While most people would dream of having enough disposable dollars to give philanthropically, it still can be daunting to begin. With 1.5 million non-profit entities in the United States alone, how do you and family members decide where to give?

There can be value in getting a feel for grantmaking by making a few grants and seeing how it goes; however, even scientists believe in formulating a solid hypothesis before running experiments. Before diving into questions about grantmaking, spend some time exploring and clarifying your philanthropic identity. Ask yourself, individually, and in tandem with other family members:

- What legacy have I inherited from my family and community? How does that legacy inform who I am and how I see the world?

- What are the values that have driven my decision-making?

- What are the pressing questions or challenges in the world that I want to address with my philanthropy? What do I hope to change or make better?

By reflecting on these three basic, yet profound, questions, you can begin to narrow your focus and clarify what and how you want to make a difference through your giving.

2. Prioritize your Motives

Many donors try to meet dual motives with their philanthropy: family unity and philanthropic strategy. They want to engage their family members in philanthropy, yet they have a clear idea of where the family will allocate funds.

From our experience in working with families, it’s hard to achieve both motives simultaneously and equally. Those donors who are unabashedly candid about which motive trumps the other tend to have better success achieving their goals.

If bringing the family together—and keeping the family together over time—is the reason you are practicing philanthropy, then invite and include family members in decision-making from the start. If pursuing a certain funding area or philanthropic strategy is your number one concern, be honest about that, and understand that some members simply might not be interested. Regardless, the clearer you are about your philanthropic motives upfront, the more you can save yourself from unproductive family dynamics later.

3. Articulate your Values

It’s natural to want to jump to ‘what are we going to fund?’ yet we recommend going slow to go fast. Start by articulating the motivational values, the core beliefs, that will underlie the family or board’s decision-making on giving, investments, human resources, policies and the like. Values also inform internal operations and communications, as well as externally how the foundation interacts and communicates with its grantees, partners and the public. We recommend each family member clarify his or her own personal values, which you can then share with one another. This often leads to a rich discussion on how others approach their giving and decision-making, and can help the group articulate values for the family philanthropy moving forward.

4. Craft a Vision & Mission Statement

There is nothing wrong with writing checks as a reaction to having your heart strings pulled, but with more than $600 billion in philanthropic assets (and more than $45 billion in charitable dollars allocated each year) in the United States alone, stating the difference you want to make through your grantmaking is a responsible way to give—especially when the needs are so great around the globe.

What’s the difference between a vision and mission statement? A vision statement is your eye toward the future. It’s the answer to the question, ‘What is the change I/we want to make in the world?’ Or, ‘what’s the legacy I want to leave?’ Your mission statement is how you want to go about achieving that change over the next 1-3 years. Allow yourself to dream up the vision you want to make possible, and then clarify what you will fund or won’t fund to achieve that dream. The clearer you can communicate your vision and mission statements, and what you’ll fund and won’t fund, the easier it will be for prospective grantees and funding partners to understand when to approach you, and for you to see clearly when something is a fit for your philanthropic goals or not.

5. Know your Giving Personality

There is no right way of being a philanthropist, but we find that people tend to have an image in mind of how they want to conduct their giving. For example, some donors want to write checks at arm’s length, even anonymously, meeting immediate needs or responding to social requests. These donors might prefer that staff or consultants represent them, rather than interacting with grantees directly. Other donors (especially next gen donors) want to be hands-on and see themselves as partners to their grantee organizations, offering time and talent as well as treasure.

Ask yourself and each family member how they envision interacting in the role as donors. Do you wish to engage with grantees and the community? Do you desire recognition, or prefer to be anonymous? These decisions can inform choices such as naming, staffing, publicity and relationships, both within philanthropy and beyond it.

6. Form your Group Identity

Do you wish to keep the philanthropy an all-family affair? Or will you invite independent non-family members to participate on the family philanthropy board or take part in decision-making? Potential candidates might include spouses and partners, children and step-children, advisors, community or funding area experts. Inviting non-family members can introduce valuable perspectives, experience and skills, as well as temper family dynamics; however, it can evolve the entity away from the family as a primary focus. It’s helpful to discuss your short and long-term intentions for bringing people on as decision makers, as well as the ideal size for the decision-making body, and the benefits and potential challenges of bringing in new people.

When adding people to the group, consider what psychologist Bruce Tuckman refers to as “group identity formation” or the stages of “forming, storming, norming and performing.” Every group, even those related to one another, must go through these stages to determine how they will interact, hold discussions, make decisions and optimize their productivity. Especially in families where patterns of behavior already exist, it’s important to mutually agree upon “group norms”—the behaviors the group ideally hopes to see when interacting. Boards that devote time to orienting and onboarding new board members, sharing the articles of incorporation and bylaws (if a foundation), establishing and revisiting mission and values statements, and carefully monitoring group norms have an easier time managing conflict when it arises. Keep in mind: It’s easier to point to previously-determined policies on group behavior then it is to point a finger at a person acting out in the moment.

7. Bolster your Legal and Fiduciary Awareness

Most donors are so excited about the honor of giving that they forget to recognize the responsibilities that accompany their opportunity to give. If you form a foundation, it is essential to educate board members about their legal and fiduciary responsibilities—to protect you, them and the foundation. If you set up a donor advised fund (DAF), the fund’s leadership is responsible for monitoring legal duties, but it’s good to inquire about their governance practices.

For example, ask how they adhere to the three big ones: Duty of Obedience means one can’t make a decision that is contrary to the organization’s governing documents or applicable laws. Duty of Care mandates that board members be well-informed when making decisions on behalf of the foundation. And Duty of Loyalty conveys that board members must act solely in the fund’s interest and not in their own, avoiding or at least disclosing conflicts of interest and maintaining confidentiality. And consider reaching out to your financial advisor to help educate successor trustees on how to read financial statements and monitor investments. This gives family members a chance to ask questions and learn from these experts.

8. Assign Roles and Responsibilities

Whether you’re writing checks around a kitchen table or board table, give everyone a role. Giving people roles can level the playing field and enable next generation family members and those with less grantmaking experience the chance to feel included by bringing their talents and skills to the table. Consider whether you want to create formal roles, such as officer for a foundation, or informal roles such as “time keeper” and “note taker” for family meetings or reviewing gifts from a DAF. So as not to unravel into family patterns, consider defining the criteria and expectations for each role. What are the skills and experience needed for the job? Who in the family, or outside the family, is best qualified to assume those roles? What are they expected to do and by when? Written descriptions further set clear expectations so that everyone shows up aware of what’s expected of them. Job descriptions don’t have to be formal; simple bullet points will do.

9. Establish Governing Process and Procedures

Organized chaos might work at home, but the more policies and procedures that are worked out ahead of time, the less conflict can arise and present fodder for family and group dynamics. For example, begin by drafting a list and discussing the decision-making process, such as:

- Who will bring grants for the family’s or board’s consideration?

- Who will have a voice in the discussion about them?

- What kind of materials will be circulated in advance of that discussion, and who will prepare those materials?

- How will the family or board cast votes? By consensus? Majority (by number) or supermajority (by percentage)?

- How many people constitute a quorum for a vote?

10. Schedule an Annual Check-up

Once all the thoughtful upfront preparation is organized, calendar an annual assessment to review how the first year has gone. While this might seem too early to think about, especially as you are starting out, it helps to instill a culture of self-reflection—a humble practice in an industry with little regulation and lots of hubris.

During your annual check up, consider how well your giving aligned with your vision and mission, and discuss if there’s a need to change direction. In year two, create a policy for an annual meeting of the board where directors and officers are elected or re-elected. Consider implementing term limits to bring in fresh perspectives and family members from different branches or generations. In year three, establish a learning, monitoring and evaluation process to measure the impact of the grants you’ve made. Annually, to engage family and other board members, invite individuals to discuss what they’d like to learn or do differently in the year ahead.

11. Plan for Succession

The hardest task for people is to imagine a time when others will carry on their life’s work without them. This is as true in family philanthropy as it is in a family business. Yet, like going to the dentist or eating spinach, succession planning is necessary for an entity’s good health.

It requires earnest planning and diligence to document plans for the future. Identify a successor or two, talk with those you hope will take on leadership after you’re gone, and capture in writing what you hope will happen for the board, as well as the grantmaking. Your next generation family members will thank you for the forethought, for involving them in the planning process, and for doing so during your lifetime.

This article is an updated version that was originally written/prepared for Family Office Association, October 2016.

Sharna Goldseker is a speaker, writer, consultant, and today’s leading expert on multigenerational and next generation philanthropy. A next gen donor herself, she offers a trusted insider’s perspective. As executive director of 21/64, the nonprofit practice she founded to serve philanthropic and family enterprises, Sharna has created the industry’s gold-standard tools for transforming how philanthropic families define their values, collaborate, and govern. She is co-author of Generation Impact: How Next Gen Donors Are Revolutionizing Giving to be published By Wiley in October. To be in touch email info@2164.net.